|

134th Infantry Regiment"All Hell Can't Stop Us" |

|

|

134th Infantry Regiment"All Hell Can't Stop Us" |

|

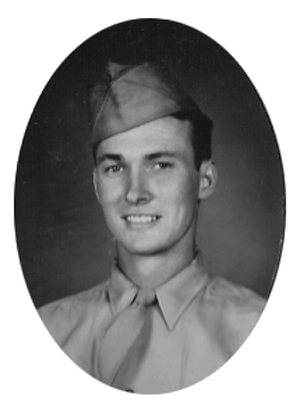

John Robert (Bob) Sirk , now age 94 and living in Grant County, Indiana, was a

Huntington County Indiana farmer and father of a two-year-old son when he was

called to serve in World War II in early 1944. He

and a high school friend, Paul Forester, left from the Huntington, Indiana,

train depot for Fort McClellan in Alabama.

Dad never talked about his WW II experiences to anyone.

His four children knew he had been in the war only because he had a

crippled hand where he had received shrapnel wounds.

In 1994 when he received a mailing from James Graff of Middletown, Illinois,

about the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge, he expressed some

interest in attending this memorial service which was to be held in St. Louis,

Missouri. Our mother, Evelyn, his

wife of fifty years, had passed away the year before, and this may have had some

influence on his need to revisit with the past.

He traveled to St. Louis in December of 1994 with his oldest son Joe and

his daughter Sue. The three of us

had no idea how we were going to connect with Mr. Graff or anyone else from the

35th Division. As we were

in line to have dinner right after our arrival, two couples were leaving the

dining room and passed right beside us.

I happened to read the nametag of one of the men and, to my astonishment,

it was James Graff. After that

meeting the rest of the weekend was spent making connections, exchanging stories

and information, and forming what was to be a friendship which lasts to this

day. My brother Joe, who was a

history teacher and avid scholar of World War II, sat in rapt attention as these

men of the 134th Infantry poured forth amazing and, previously

unknown to us, powerful recollections of the Battle of the Bulge and the events

leading up to it. One very curious incident occurred during this trip to St.

Louis when the three of us were at the famous St. Louis Arch.

Since each of the cars carrying tourists to the top of the Arch held four

people, there was a fourth person in our car.

Joe recognized him as the historian Stephen Ambrose.

When Dad was introduced to him, he asked Dad about getting replacement

boots during that terrible winter, and Dad replied that he did get new boots but

only because he had very small feet.

This convinced Ambrose of Dad's account of his experience, since he knew that

those soldiers with a more common shoe size had a much more difficult time

getting dry boots, and, as a result suffered terribly from frostbite.

After attending the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge in St. Louis

in 1994, he has made it a point to talk with his children, grandchildren and

great-grandchildren about his war experience whenever he was asked about it.

He recounted his experience to the Veteran's History Project sponsored by

Senator Richard Lugar, and he has returned to the sites of his experiences in

1944 on three occasions. In 1985, he returned to France, Belgium and Germany

with his daughter, son-in-law, and grandson.

In 1998, he and his son Joe joined a group of veterans from the 35th

Division for a return trip to Bulge sites, and in 2004, he and his daughter went

on the 60th Anniversary tour organized by the VBOB.

One of Dad's most vivid memories of basic training wasn't of weaponry or

strenuous physical demands, but of sharing a hut with some fellows from Kentucky

and Tennessee who had never had formal schooling, and, for whom, some of the

basic literacy skills were challenging.

If all of them could not write their names or memorize their serial

numbers, they all had extra latrine duty.

In the fall of 1944, after being shipped to England where, according to his

memory, he walked down the gangplank of one ship and immediately up a gangplank

of another, he was among the group whose arrival on Omaha Beach was the last to

be landed from a landing craft - an LCI.

They

waded through water and climbed the steep cliff to a

replacement camp on top of Omaha Beach, and he vividly remembers it was midnight

before he got dry. His group

proceeded forward on a "40/8" cargo car

to Nancy, France, where, on November 18, 1944, he joined the 35th

Division, 134th Infantry, Company C. He began the march through

France, to Morhange, where on November 22, the first battalion in reserve, of

which he was a part, ate a Thanksgiving dinner.

Near the town of Puttelange, with Capt. William N. Denny commanding

Company C, Dad remembers moving into

the first of the Maginot Line bunkers.

One of the most intensely painful events of Dad's march through France before

the outbreak of the Battle of the Bulge occurred as his company was approaching

the town of Fraunberg near the Bleis

River. His group had stayed in a

house with an actual bathroom the night before moving forward across a sort of

railroad yard with several sets of tracks.

As they crossed this area with no cover, they came under fire.

They then prepared for the crossing of the Bleis River from Sarreguemines

on the French side to Habkirchen on the German side in engineer assault boats.

The first boat which started to cross leaked and rapidly took on water,

so it returned, and the rest of the guys "took off back to the house" where they

had stayed the previous night. Capt.

Denny told Dad to get in his boat and go with that second group of men.

Dad had already lost his warm overcoat (later seen as good luck because,

had it been on, it would have dragged him down in the later river accident).

They started across the river which had

been dammed up, but the boat capsized when it hit a concrete abutment and went

down just as they came under fire. He was

able to grab hold of a low hanging limb, but another man grabbed his legs, and

they both went in the freezing water - winter clothing, rifle, everything.

Having no heavy overcoat probably saved

his life, and he and a small group of men from Company C made it to shore and

went up the bank into a house in Habkirchen. At this time the German defenders

were awakened, and Companies C and D were all alone with no supplies--no heat,

no food, no way to dry out except by just wearing the wet clothes.

Because he was wet and had no rifle, he was eventually sent to the

basement to guard prisoners which had been taken as they gained control of this

house. Someone had given him a

handgun, and, as he was at his assigned station, an officer came downstairs.

When Dad asked him for the password, his response was, "Damn it, soldier.

I forgot the password." Because

there were a few soldiers from Company B in another house across the street,

some of the guys went over there while

maintaining radio contact between the two houses.

In the meantime there was enemy fire, and, because the bridge had

collapsed, a reduced number of Companies B and D joined

most of those who had

survived in Company C in this house. Denny sent some, including Dad, over to

help the Company B guys in the second house across the street, but they came

under enemy fire and were ordered to return immediately.

At one point during this time of action

in Habkirchen, there was a sort of temporary truce after a particularly vicious

exchange with the SS troops (who had refused to be taken prisoner along with the

other Germans in the basement), and, according to Dad's memory, a German doctor

who could speak English was allowed to enter the house to attend to the German

prisoners and was afterward allowed to go back.

Ultimately, Capt. Denny had 21 men left in the house with about 65 German

prisoners in the basement--a portion of the few Germans

who had hoped to hold on to this spot in Germany.

By this time, Dad was back up in the top story when a large group of

60-70 SS troops came down the street.

It was getting darker and, when ordered to fire on them, the enemy could

see flashes of the guns and returned fire.

Dad and another soldier crawled on their stomachs down the stairs to a

lower level as the Germans fired into the upper story. When recounting this

event to his oldest grandson, Scott Sirk, he found it very painful to recall

firing at the German soldiers and living with the guilt he felt about killing,

even though killing the enemy is a part of war.

The next day, by which time Dad had gotten a winter overcoat and rifle, probably

belonging to a casualty, they were sent out to take the high ground

above

this town of Habkirchen from which rounds of 88 artillery had been firing down

into the town and to the house where what was left of Company C and a few of

Company B and D were. This fire was

probably from the 17th SS Panzer division which were in the nearby

woods. As they made this approach, they again came under enemy fire and were

ordered back immediately. Dad and another infantryman named Pulaski, a great,

oversized guy, both started running back to safety, and the big guy yelled,

"Sirk, you're not leaving me behind, you little shit!" and started ditching his

gear to keep up.

Finally, 17 more prisoners from this panzer division were added to the big group

of 60-70 already in the basement.

This action garnered Company C a presidential citation after the war.

In this action, over three days, there were 680 wounded or injured and 142

killed, necessitating reinforcements of around 500 men as replacements

At the fortress city of Metz, Dad's unit was relieved by 44th

Infantry Division. At this same time

- the 15th, 16th, and 17th of December, 1944,

100 miles away, Germans were starting the Ardennes Offensive, later known at the

Battle of the Bulge. It was about

this time that General Patton hurriedly turned his army around to head to

Bastogne.

Back in Metz, Dad and others got showers.

Dad recalls standing in freezing water with warm water pouring over his

head. He then received replacement

boots of rubber,

but only because, being a smaller, wiry guy who had small feet, these better,

warmer, sturdier boots near his size were available.

Others with bigger feet had to take canvas ones and later got frostbite.

Within a short

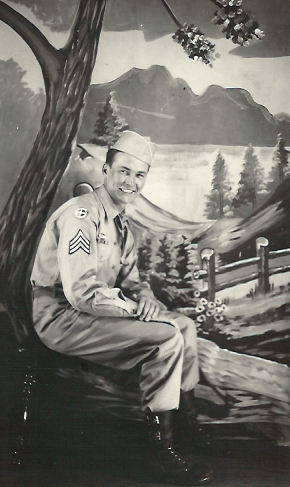

span of 13 days, everyone else in Dad's squad had been replaced, and Dad,

as a result, had the longest combat experience, so was named squad leader after

just this short time; however, his promotion to staff sergeant didn't come

through before he was wounded and sent to a hospital UK.

When the German offensive, later known as the Battle of the Bulge, broke out,

what was left of Company C were ordered to Bastogne. After Christmas day, Dad

and others were trucked to Arlon.

The next day, December 27, they were

marching alongside tanks from the 4th Armored Division which were

trying to keep the road open so that supplies and reinforcements could reach

Bastogne. By December 30, Company C was

in the tiny village of Marvie, very near Bastogne. Dad's unit had relieved the

101st which had dug in and

spent two to three weeks around Bastogne holding the German offensive at bay.

It was the job of the 35th

to continue to hold this spot from the Germans. It was on this day that Dad

received the wound to his right hand from an 88 artillery shell

as he was running back to his foxhole

after being sent forward to assess the range of the US guns. The Germans were

ensconced across snowfields and meadows, and Dad was told to go down a fencerow

to see where Allied mortar fire was

landing so he could tell his unit whether they were hitting long or short.

He had done two trips, getting close enough to hear Germans talking

very late at night and was returning from the third just as dawn was

breaking. In this light, the Germans

spotted him and fired. When he heard

the 88 artillery coming in, he

jumped into a foxhole, but was hit in the right hand by exploding shrapnel from

the shell.

When the medic came to help him, he said to Dad, "That's a million dollar

wound." Dad didn't know what that

meant, only that he was hurting. He

was taken back to a field hospital and, from there, transported to a hospital

near Exeter, England. Because he was

mobile with no injury to his legs, he helped other wounded soldiers in various

ways. He has a vivid memory of

waking up after surgery there and looking at a brace on his arm where he read

"W.E. Zimmer Mftg, Warsaw, Indiana."

After his horrifying and traumatic experiences of recent weeks, he felt like a

little piece of home had come to his aid.

Many years later, Dad and Mother stopped by the Zimmer Company in Warsaw and

related this story. Dad was asked if

by chance he still had the brace because they would have loved to have it as

part of their historical display.

When the subject of his World War II experience has come up in the recent years

when he was willing to talk about it, he always says, "Well, I was one of the

lucky ones." He seems to have spent

his life believing he was afforded a certain grace, and he has lived a very

modest life of quiet gratitude and deep appreciation for just being alive. He

never complained about tenant farming for over sixty years in all kinds of

weather; each day out in the fields or

working among animals reminded him that his life was a gift.

|

|

Thanks to Sue Landaw, Sgt. Sirk's daughter, for the pictures and informaton about her father.

|

Sign Guestbook

|