|

134th Infantry Regiment"All Hell Can't Stop Us" |

|

|

134th Infantry Regiment"All Hell Can't Stop Us" |

|

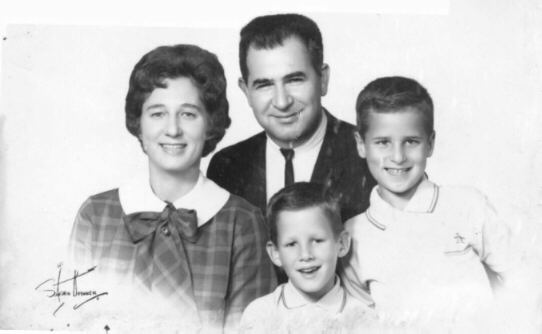

Robert ("Bob") Goldstein

1st Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion

Photo taken in 1943

July 1944 Journal of Robert ("Bob") Goldstein Pvt 1st Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 134th Regiment

Introduction: My late father, Robert ("Bob") Goldstein enlisted in the Unites States Army after graduating high school. In 1943 after basic training, Bob found himself as one of the youngest soldiers in 1st Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 134th Regiment, 35th Division at Camp Rucker, Alabama. Bob trained in the United States, traveled to Penzance England and landed in France with the remainder of the 134th Regiment. When Bob arrived his France he wrote down the daily events. Apparently keeping journals in combat was against military regulations and his account was first read in July 1944 when Bob wrote letters to his parents from France. Each daily letter told the story of the events one year before. When read together they become a detailed narrative of the first combat of the 134th Regiment.

Bob’s narrative lay unpublished in our home for 45 years. He told his children his account of the first battle of the 134th Regiment was private. As you will soon read, Bob was severely wounded on July 15, 1944 in the assault on Hill 122 north of St. Lo by the 1st Battalion. In late 1999 complications from his wound began to end his life. In the year before his death he gave permission for his journal to be published and even sent a copy to historian Stephen Ambrose.

I am grateful to Roberta Russo for posting Bob’s narrative on her web site. Ms. Russo has also done a great service by transcribing Colonel Butler Miltonberger’s history. Because Chapter IV (Normandy) of Colonel Miltonberger’s history and Bob’s narrative describe the same events (although from the perspective of a Colonel and Private, respectively) I have decided to introduce selected portions in Bob’s narrative with a quotation from Colonel Miltonberger’s history.

In reading the narrative, please note that Bob’s entries are in regular type, quotations from Colonel Miltonberger are in bold type, and my comments are in italics.

Mark H. Goldstein, Las Vegas, NV July 4, 2001

(July 5, 1944)

Combat History of Word War II, Chapter IV Normandy, By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois,

Regimental Headquarters established its first command post in France –– in Transit Area 3 –– at 1545 on 5 July, but the C.P. moved to an area near Mercey that night, while other units of the Regiment continued to come ashore and make their way to the assigned assembly area. That night marching columns and motor convoys moved through the light of the near-full moon. Overhead an occasional Nazi plane would set off a tremendous –– and beautiful –– anti-aircraft barrage. The white moonlight lent a ghastly appearance to the crumbled stone and mortar houses of a destroyed village through which the columns moved. "It looks exactly like some of those old movies of the World War," someone observed.

6 July 1944

The weather was exceptionally nice (except for a quick shower in the afternoon). One of the first things we did after awakening was clear ourselves protective ditches in a natural gully. With water from nearby wells we washed and then sunned ourselves. Our outfit was lucky; they brought our duffle bags to us. Very few outfits saw their duffle bags. We got out clean underwear and socks, took off our gas protective impregnated clothing, and got rid of excess material. I believe we even played a few games of checkers. We brought a much-worn board to the continent with us--the same one we used on the ship coming to England.

About four that afternoon we were ordered to a new assembly area. It was hardly more than a mile away. Our entire company was placed in along the hedgerow perimeter of a medium-sized field. Again we used natural gullies along the hedgerows for protection and stretched our shelter halves over us for over-head protection (from the weather). We slept well that night except for anti-aircraft fire which woke us about four o’clock in the morning.

7 July 1944

One year ago today the weather was a mixture of bright sunshine and sudden showers. Everybody seemed to be having his hair cut that day and I was no exception. Some had all their hair cut except for a V of hair; others had a rim of hair left around a bald spot; some had division patches cut from their hair; others had scalp locks; some just had small round plates of hair left on top of their heads.

I was one of the group that had all his hair cut off--down to the scalp. The only way it could have been any closer was to have been shaved.

I have to admit that I did look funny but my head was comfortable especially after it got a brisk washing. (It was only until after I was in Hoepertingen a while that my hair came back to normal.)

Nothing else much was done the rest of the day. That night at about eleven o’clock--a plane came over. It must have been jet-propelled because we couldn’t hear its motors but we could see its lights. Why its lights were burning I don’t know unless it was to draw fire from the anti-aircraft to discover its position. It did draw AA fire all right and plenty of it but I don’t think it was hit.

We slept quite well that night anyway.

Combat History of Word War II

, Chapter IV Normandy, By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

The 35th Division was about to be committed, but the 134th Infantry (less the 2nd Battalion) was being held out for the time being as corps reserve in Major General Charles H. Corlett’’s XIX Corps. The two sister regiments, the 137th, under Colonel Grant Layng, and the 320th, under Colonel Bernard A. Byrne, were to make a limited attack in a zone to the left (east) of the Vire River between La Meuffe and La Nicollerie. (The Division was going in between the 30th –– "Old Hickory" –– Division, on the right, and the 29th –– "Blue and Grey" –– on the left.) The 134th now was moving up to an assembly area where it would be available for action on short notice.

In the new assembly area (the C.P. was near Les Essarts) all companies immediately set themselves to preparation for the problems ahead. For some unexplained reason (it might be explained on the basis of security prior to 6 June, but certainly not after that date) there had been no instruction or suggestions during the period of training in England concerning the tactical implications of a terrain characterized by such a system as hedgerows as was to be found in Normandy. Although the Cornish countryside was broken into small fields by systems of hedgerows, thinking had not gone much beyond the stage of speculation. But now the problem was real. It could be seen that the defender was going to have some advantages.

The hedgerows were similar –– banks of dirt, sometimes with stones in them, as much as three to five feet thick at the base and tapering gradually to a thickness of two or three feet. This embankment usually was four to five feet high and surmounted by shrubs or trees. The sides were covered with grass and shrubs. The origin of hedgerows remains rather obscure, though it is likely that the scarcity of building materials (many of the houses are made with wooden beams and earth), and the rich soil and climate (which makes plants grow rapidly and thickens the hedges) contributed to their development. There are said to be two kinds of hedges there, the quickset and the dry hedges; the first were by far the most important, and they, in turn, were divided into hedges of defense, shelter, orchard, and fodder. Built for the protection of property, the defense hedges usually were made up with thorny shrubs; shelter hedges also were defensive, but had the further purpose of serving as windbreaks, and their timber yielded wood for building or heating. If the trees were for producing fruit, then the hedgerows were "orchard," and the fodder hedges contained any number of varieties of shrubs and trees. The hedgerow system seems to have dated at least from the time of the Romans. Now the main purpose of the hedgerows, whatever their origin, came to be protection against shellfire and bullets. In any case those earth and plant fences enclosed fields –– usually meadows or orchards –– of irregular shapes and sizes which seemed to average toward a rectangle about 100 yards long and 50 yards wide. "An aerial photograph of a typical section of Normandy shows more than 3,900 hedged enclosures in an area of less than eight square miles."

8 July 1944

One year ago today the weather was not so nice. It began cloudy and by noon time it was raining. We were made the corps reserve and were ordered to a forward assembly area. The load of equipment we had on our backs was heavy but we were so used to that that it didn’t bother us. But the rain-soaked roads were so muddy that we sank half way to our knees. We didn’t realize how close we were coming to the front until some hidden cannons about five hundred yards or less from the road fired over our heads. The first volley really scared us. After that we moved so far in front of the artillery that all we could hear was the whistling of shells over our heads in the direction of the Germans.

The place we stopped at was at a crossroad village—I’ve forgotten the name. Two platoons of our company were assigned a small orchard for a bivouac area. We were told to dig in before dark. That was about four-thirty in the afternoon. We thought we had plenty of time but by the time we stopped digging it was dark. The topsoil was soft but the undersoil was real rock. The owner of the orchard seemed to object to our digging at first. He was raving mildly in his Norman "patois" which I couldn’t understand. We had a French-Canadian in the outfit who engaged him in conversation and within 15 minutes the Frenchman was helping the soldier dig his slit-trench.

There was a lot of long loose grass under the apple trees and we used it for camouflage. I’ve never seen a better piece of camouflage even in a training film. Only by stumbling on it by mistake could anyone have discovered us there.

All the security went for naught when during the night the usual German plane "bed-check Charlie" came over. Some one near the area opened up with a 50 caliber with tracers. Luckily the plane didn’t attack. The rest of the night was uneventful.

9 July 1944

Last year at this time the weather was fairly nice. We did hardly anything except clean up. Of course our rifles received first priority in the respect. We stripped them down to 20 odd pieces, cleaned and oiled each one individually, careful to keep oil out of the chamber or off the face of the bolt. We cleaned our clips and each round of ammunition individually. No one hounded us to clean our weapons, there were no inspections; we did all that voluntarily.

All went well that evening.

10 July 1944

(July 10, 1944) Combat History of Word War II, Chapter IV Normandy,

By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

When the Division made its initial attack on 11 July, each of the battalions of the 134th was permitted to send a limited number of officers –– limited so that they would not interfere with the operations of the units –– to observe the action

. . .

Rifle platoons, during those last days of training, practiced at making attacks in which the squads used their Browning automatic rifles to "spray" the hedgerow running parallel to the front while a few men with grenades worked their way up the lateral hedgerows. Sometimes a squad would remain at the base of fire while the other squads worked forward on either side of the hedgerow toward the front, or sometimes smaller groups would work forward, always with support of machine guns.

Last year at this time (with the weather a little better) we were across the road in a field to practice hedge-row fighting. Our platoon sergeant the day before had been ahead with a company of another regiment of the division (320th) to observe tactics and he was passing his information on to us.

Of course from day to day tactics change and we never actually used what we practiced.

During the afternoon our lieutenant took us into another field for calisthenics--grass drill, etc. We weren’t in the best of shape. The rest of the day was uneventful and we devoted spare time to rifle cleaning and washing. The artillery which had moved close behind us during the day was sounding off loudly during the night but that noise didn’t bother us.

11 July 1944

One year ago today I was also on the search for food. I wasn’t too successful although several fellows came back with liquor (the Calvados being a little stronger than the stuff to which they had become accustomed), and several fellows even came back with slices of freshly cut steak.

Mail had come in that day, too--a large amount of it. I received a generous share myself. We also were given access to our duffle bags which had been stored away with our gas masks in a battalion storage area. Clean clothes were a relief but I had to wash the dirty clothes I took off. I also got a hold of "King’s Row" which I began reading that day.

Our excellent camouflage was gradually disappearing. The front was moving forward and we were becoming more careless. We all pitched tents completely above ground and our grass covering was neglected. Even the unripe cider apples were beginning to disappear.

That night, the artillery which had been moving up further during the day, was firing either even with or ahead of our position. It was a restful night.

12 July 1944

July 12, 1944 Combat History of Word War II, Chapter IV Normandy,

By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

Other final preparations included the disposal of excess baggage. All clothing and equipment that was not going to be used was put into duffel bags, and all these were collected and placed in the custody of Captain Albert B. Osborne of Service Company. All gas masks were collected and stored there. Whenever a piece of extra or superfluous equipment appeared, the supply officers would call out immediately, "Send it back to the duffel bag area!"

. . .

The only fresh troops remaining to influence the situation of the XIX Corps in its battle for St. Lo with the 134th Infantry Regiment, and now General Corlett had determined to commit this Regiment in an effort to break the stubborn German defenses.

A year ago at this very hour I had just begun to relax after packing my equipment. We had received orders earlier in the day that we were to move out that night. So during the day we washed thoroughly for the last time, got rid of excess equipment, gave a last minute checkup on our weapons and then relaxed. I read a little more of "King’s Row." About 10:30 P.M. our lieutenant called us together to give us the orders. Previously we had been told we were going to bypass St. Lo., go beyond it and then cut over to the Brittany Peninsula. As could be expected from the army, our orders were changed. I don’t recall exactly what the orders were but I think it was said that the other two regiments were having difficulty pushing to St. Lo. (as well as other divisions). As corps reserve we were called in. Our move that night was supposed to be secret.

Secret!! If the Germans didn’t know we were coming it was their own fault. It wasn’t our fault, though.

We did all we were supposed to do. No one spoke; if we had to talk we whispered. We didn’t crowd together nor stray behind. But we were forced to walk on each other’s heels, one shell would have killed half a company. Tanks and Tank Destroyers forced us off the roads. Their noise disclosed our position. Cannons off to the side frightened us (that is the sudden shock) with their close blast and that same blast illuminated our position. Everything was so typical.

We marched for nearly five hours--got only about 10 miles. They finally found us a field to stay in. It was so dark we couldn’t actually tell where we were digging. Another fellow and I tried to dig a two-man slit trench, By the time it was light we laid down to sleep.

13 July 1944

{Bob notes: I have no letter for this date. If I did write one, it was not kept by my parents. Many years ago, when I first reconstructed this narrative from the longer, personal letters, I had no recollection of the events on this day in 1944. I assume, therefore, that it was a relatively uneventful day.}

14 July 1944

Combat History of Word War II, Chapter IV Normandy, By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

Impressed with the weight of the support which was to be given in this delivery of the "Sunday punch," the tanks, the tank destroyers, the tremendous artillery rolling barrage –– a concentration on this narrow front which would include not only the 105mm fire of the 161st Field Artillery Battalion and Cannon Company, but also the reinforcing fires of two medium battalions (a total of twenty-four 155mm howitzers), the 127th from Division Artillery, and the 963rd from corps, leaders departed the meeting with full confidence that the German defenses would break before their attack.

The noisy armor rumbled into forward assembly positions during the night, and, fortunately drew little artillery fire. The 1st and 2nd Battalion prepared to go.

About this time last year we were re-reading special letters which we saved up until the last moment.

I read a little more of "King’s Row" which I had to leave behind with my letters. We signed the payroll that day, too.

Later in the afternoon some fellows from our artillery were passing through. They had been at the very front observing for their batteries. We took some hints from them. We were eager to listen to anybody who had been at the front.

In the field next to ours were two deserted farmhouses. By one was a rabbit pen with live large rabbits in them. The doors to the cages weren’t locked but the rabbits didn’t bother to escape. We opened the doors for them, some went out, nibbled a little grass but soon returned. I don’t know if their masters ever returned.

Just before it grew dark some artillery C.P. was setting up in that field next to ours. We noticed they had musette bag suspenders which would come in very handy in supporting our overloaded cartridge belts. The artillery men didn’t hesitate to give them to us. We went to sleep early that evening because we knew we were to be awake at 2 A.M.

15 July 1944

Combat History of Word War II, Chapter IV Normandy

, By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

Hill 122, then, was the immediate objective as the men of the 1st and 2nd Battalions moved, in well-deployed formations, throughout the area of the 3rd Battalion and through the artillery which already was falling, toward that last hedgerow short of "no-man’s-land," toward that spot which becomes the last lot for all infantry riflemen, where there is nothing out in front but the enemy.

The attacking men tried to escape the thought which impressed itself upon them, that this first day of battle would be the last for some of them. They were under no delusions concerning the task which they faced, but the training, and discipline and leadership would admit no faltering now. They saw wounded men of Company I and Company K, but it hardly occurred to them that this and worse might be their own fate. Perhaps there was a trace of cold sweat at the temples and in the palms of the hands, and a tenseness in the stomach and dryness in the throat, but they pressed on with an increasing momentum toward the hedgerow which would be their last barrier to the bullets of enemy fire, and, reaching it, they began to scramble over, unconscious of the pricks and briers or even of the weight of their equipment . There hardly was a moment for adjustment of thoughts once the men were moving toward the enemy positions. The demoralizing high-speed machine guns began to chatter furiously, and shellfire –– mortar, artillery, high-velocity, direct-fire "88," became even more overwhelming.

. . .

It was the enemy shellfire which was causing the greatest difficulty. Small arms fire, and especially rapidly-firing machine guns and the hated machine pistols ("burp guns"), to be sure were troublesome enough, but those weapons could be maneuvered against, or brought under fire, or possibly avoided, once their location was determined. But against artillery fire there was that feeling of helplessness which grew out of the inability of the infantryman to undertake any direct action against it. The only thing to do was to move forward, and that was possible only with the benefit of a trained discipline.

Casualties were mounting. But men . . . could not be aware of how heavy they were. It was not always a picture of thin lines of advancing men growing thinner as men fell while the others continued marching. One did not really see very many men fall. Many of them were caught as they lay in foxholes or behind hedgerows. Others, of course, were caught as they moved forward, but few really saw it happen because their view was hidden –– again the hedgerows –– from those a safe distance away, and those who were close were themselves dropping to the ground in an effort to find protection.

Last year at this time the weather was equally clear but not quite so warm (climatically speaking). It turned out to be a hot day for both us and the Germans.

We were awake at 2 A.M. Normal anxiety kept us from being sleepy. However, no one was scared, that is no one seemed scared. We turned in our packs and blankets and everything we didn’t intend to carry with us. As much as we did strip ourselves down we still had a lot to carry. Our uniform was O.D.’s and our division patches remained on. Our jackets were worn inside out to prevent possible shine on any smooth surface of the jacket. We darkened the white on the patches for the same reason.

Our cartridge belts were loaded with ammunition and hooked on to mine were first aid packet, canteen, entrenching tool (pick) and bayonet. Also draped over the back of the cartridge belt was a folded raincoat. Slung over one side was an ammunition bag in which I carried hand grenades, rations (K), extra socks, a few toilet articles. And lastly were two bandoliers of ammunition.

Lt. Kjems our platoon leader had been at a meeting and returned to gives us our orientation or plan of battle. It was done dramatically and almost in a Hollywood style. Lt. Kjems had studied dramatics and could always put on a good show. But this time it was necessary. He had to read his notes and to hide the light he had to read them under his raincoat. He was down on the ground, two fellows holding his raincoat over him. To add another factor to the melodrama it was pitch dark except for an occasional shell flash. We couldn’t see him but we could hear his voice coming, it seemed, from the ground.

I’ve forgotten the details of the plan but our immediate plan for the morning was (for the battalion) to move through the third battalion lines and forward. I can’t remember the details for other outfits. Our company had the lead in the attack and our platoon was to lead that. The second and third squads had the lead, our squad followed behind for cover, support and reserve.

The kitchen was late in setting up but we did have a little breakfast about 3:15. Then we were on the way.

We had a swift march which took us forward several miles but as usual someone took the wrong road and accidentally headed back in the direction we came. In the meantime, an increased artillery barrage kept the skies lit almost constantly.

They finally took us in the proper direction to a forward assembly area. We scattered in a small field. It was about 4:45 A.M. In the field near me was a Chinese fellow Sieow Gee. He had been in the kitchen since he joined the outfit in Camp Butner. He had never had an M-1 in his hand before.

At five o’clock there was supposed to a 15 minute heavy artillery barrage. The barrage didn’t begin but at five o’clock sharp we move down a sunken road to the exact position we were to move from. At 5:10 some artillery did open up but not much.

Lou Mattes, my squad leader, was looking over the edge of the embankment even though bullets and tracers were whizzing directly overhead. Lou, as well as the rest of us, used to talk of how scared we would be when the time actually came. But Lou didn’t look scared and no one did. I can honestly say that I wasn’t scared, much to my surprise.

The other squads had already moved so Lou grabbed hold of a thorny bush and pulled himself over the embankment. I followed and then the rest of the squad.

The next few minutes were just like maneuvers--except that live ammunition was flying all around us. We would make short dashes, hit the ground, wait until the others moved up. We were deployed in a skirmish line, that is, the squad moved forward in an extended but irregular line.

Our first obstacle was a very low hedgerow with very little growth on it. We had reached it almost simultaneously and as we hit the dirt before it mortars dropped all along it. They were just the small mortars (50mm) but extremely accurate and the Germans had the range on every hedgerow. Although they burst just a few feet in front of our faces they did absolutely no harm to us. Ironically, some men in other platoons waiting to move up were hit by a deeper mortar barrage.

After the first barrage hit the hedgerow we didn’t waste a moment in getting over it. We moved quickly through the knee-high grass in the next field. In a short time we reached the next hedgerow where the advanced elements of the 3rd battalion were dug in.

This hedgerow was high and long and heavily overgrown. About 2/3 of the way from the left was an opening (probably where a gate should have been) which was blocked by barbed wire and very likely covered by machine guns. We were taught to avoid those places. I was to the right of the opening and pretty far to the right of the field.

The part of the hedgerow that I approached was very high and overgrown and I knew I couldn’t get over it in the necessary speed. I turned around and looked quickly for another spot. My back was turned to the hedgerow when it happened. The falling mortar shells make very little noise especially when coming from directly overhead. Naturally I didn’t hear it coming and as my back was turned to the hedgerow (very close to it) the mortar shell hit the hedgerow just about waist high. The blast threw me forward and up and in that split second, I saw a medic going through the break in the hedgerow and I screamed for him and then fell back.

I was never totally unconscious but I was dazed to the extent that I remained perfectly immobile. I saw a few soldiers moving forward and they may have seen me but in the position I was they must have thought that I was dead. And I gave myself up for dead. That’s no lie, I was completely resigned. I never felt more calm and at ease as I did then or during the whole day in fact. Well, I’ll stick to the events and eliminate the thoughts.

After nearly an hour (It was about 6:00 A.M. when I was hit) I began to clear up a little and noticed that my cartridge belt and clothing were restricting my breathing. I was able to unbuckle my cartridge belt but I couldn’t move my arms in position to take off my field jacket. So I took out the knife I had in my leggings (the hunting knife of boy scout variety that Aunt Ruth & Uncle Max had given me for a birthday present long ago.) I remember in England one of the fellows asked me for it (to buy it). I told him the only way he could get it was if I got hit. We made a pact that he should be the one to get it in that case. I later found out that he had been killed on the same day. I used the knife to cut my field jacket and shirt. I felt a little better.

I remembered the warnings we got in first aid classes to take sulfa pills as soon as possible. I had an extra pack (8) in my shirt pocket and was able to get it easily enough. I took my canteen from my cartridge belt and removed the cap. The canteen fell from my hand and most of the water spilled out before I could find the cap again. The blast had broken the chain connecting the cap to the canteen. When the canteen fell the cap rolled almost out of reach.

I figured I had enough water to take only one pill (after the St. Lô battle the medics advised to take sulfa even if water wasn’t available despite the toxic effect of sulfa without water). Before I drank I felt blood under and behind where I was sitting so I wanted to see if there was much internal damage. I spit up several times and no blood came out so I figured that it was safe to drink. The water I drank then was the only thing I had in me for the rest of the day.

A little while later two men who were coming up from the rear happened to see me. They walked over but passed me. I think they thought I was dead even though my eyes were open. They walked about 15yds. beyond where a fellow lay in a shallow foxhole dug into the hedgerow.

I hadn’t seen him before. He must have been hit by shrapnel from the same shell that got me. They bandaged his shoulder and ankle. I made enough of a motion to signal them over to me. They asked me where I’d been hit and I told them.

They had to pull be forward and lay me on my stomach. It was painful but necessary. They took my first aid packet and put the large bandage over my wound wrapping the string ends around my chest. They turned me over on my back to make me comfortable. I wasn’t comfortable there. I had trouble breathing. I had them sit me up as I was before. That was a painful procedure but the results were worth it. However the pain threw me into a slight case of shock and I wasn’t able to speak. My speech was all that was affected. I tried to tell the fellows to make me comfortable but I just couldn’t speak. My can wasn’t comfortable. After a few incomprehensible gestures on my part they gave up because they had to move on. I was so mad when they left that I began to curse them and that broke the spell. I was able to speak again.

I couldn’t blame the fellows for leaving because several mortar shells hit nearby several times and they had to hit the ground. I looked at my watch when they left. It was 9:00 A.M. I looked at it again about an hour later and it showed 9:05 where it stayed for four months.

Incidentally I had been knocked into the sitting position and except for the few minutes while those fellows were dressing the wound I remained that way until I was finally picked up. I was comfortable in the position except for the right side of my rear end which was bearing all the weight. I couldn’t move from that position. I tried to move by grabbing on an overhanging bush, lifting myself and dragging my entire body along. It just didn’t work because when I stretched my back it seemed to hurt me internally. I just couldn’t slide my body along. And when I leaned my back away from the hedgerow, I had difficulty breathing. But I wasn’t very uncomfortable just sitting there. I removed my helmet which hadn’t been blown off my head. However, every time I moved my head, I would knock dirt down my back into my wound so I kept my head as still as possible.

Combat History of Word War II, Chapter IV Normandy,

By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

Small shells were bursting along the adjacent fields, on the tops of hedgerows, and then down the road . . . Large caliber mortar and light artillery shells began to burst all around –– they had a way of hitting the tops of hedgerows, and, bursting in red flame and black smoke, would send fragments and dirt on the men who were seeking cover in the shallow side-ditches below. Wounded men –– those who could walk –– began moving to the rear.

While I sat there, mortar fire fell intermittently. Very often they fell right along the hedgerow some directly over my head. Those that exploded above me didn’t bother me but the ones that fell in front of me worried me some. One fell no more than ten yards in front of me. All I could do was pull my raincoat over me to protect me against the falling dirt. No shrapnel ever touched me.

After those two fellows left me I was completely alone for nearly two hours. No one was near in the entire field. The only living things I could see were some cows in the distance. They were unperturbed by the mortars.

About eleven o’clock several fellows from my company wandered back carrying two wounded fellows with them. I tried to yell to them but I don’t think my voice carried more than ten feet. However one of the fellows noticed me and came over to me. He wasn’t able to take care of me but he promised when he took the other fellows to the aid station, that he would send someone after me. He returned about 45 minutes later. He said that aid would soon come. They took my rifle, planted it in the ground (bayonet stuck in, of course) tied a white handkerchief on the butt of the rifle. That is always used to point out a wounded man to the aid men following the troops. Then he left.

Again all that was in the field besides myself and the other wounded man were the cows. They came close to us and deposited their manure almost on top of the other fellow.

Again the mortars opened up in quite a barrage which I was able to ignore until one landed about seven or eight feet in front of me. It was a dud and failed to explode.

The sky darkened later in the day and I was hoping that it would rain. I thought it would be comfortable. However the skies stayed grey and the rain stayed back.

All of the time I was out there only one thing frightened me. (That mortar dud happened too fast to scare me.) I noticed something apparently crawling in the grass. I couldn’t discern the form but it looked suspiciously like a man in a camouflaged suit. The wriggling form drew nearer and nearer and I grew more scared. Finally the form showed itself to be several small pigs walking very close together. I felt better.

I tried yelling several times for help but my efforts were too feeble. I just couldn’t get any power. The other fellow despite his wounds decided to try to make it back to the aid station on his own. I told him to try to get somebody back to me.

I was still comfortable (except for my rear end), I wasn’t hungry, or even thirsty. My wound didn’t hurt except when I tried to move.

It began to grow dark and I began to give up hope of receiving aid. Although I didn’t think I was bleeding very much, I began to doubt if I would survive the night. I had been hit about 6 A.M. and it was then about 11 P.M. (when it got dark then). Not only that, I had no way (except for suicide hand-grenades) to defend myself in case an enemy patrol came upon me. The rifle was stuck in the ground and I couldn’t dislodge it. I could see tracers aimed at the hanky tied to it. I yelled whenever I thought I heard footsteps in the hope that someone would find me. As it grew darker I began to fear yelling because I couldn’t tell whom I might attract. It had been a long day for me and I decided to try to sleep. I must have dozed off a little after midnight.

16 July 1944

Combat History of Word War II

, Chapter IV Normandy, By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

Captain Carroll remained forward long enough to check the positions of the companies, and then he made his way back to the battalion C.P. - a line of foxholes behind a hedgerow just south of Villiers-Fossard.

. . .

Twilight was adding its shadows of gloom to the already grotesque pattern of shelled and torn Villiers-Fossard when someone came up the road near the 3rd Battalion C.P. to say that there were some wounded men in a disabled tank about a thousand yards to the front. . . . . .[O]ne of the medics, volunteered to go after them. Without allowing time for any refusal, he jumped into his jeep and took off. . . . . His work was typical of the medics. All of them had won a high regard for themselves in the hearts of the doughboys. This regard was especially keen for the company aid men (one for each platoon when they were fortunate enough to be at full strength) who, unarmed, went right along with the rifle platoons and crawled from one wounded man to another to administer first aid. They were men like T/5 John S. Bradny of Ohio, who had been working unceasingly with Company A and the 1st Battalion in the most advanced positions. (At one time, in fact, he had been the only aid man present with the elements of three companies which were pinned down by enemy fire).

I must have slept for several hours in that sitting position. I was awakened several times during the night by muzzle blasts from what I judged to be our own 4 inch mortars in an adjacent field. I had difficulty returning to sleep because my rear end was so uncomfortable.

At that time of the year, dawn came early. When I awoke after my fitful sleep it was light and I judged the time to be about 6 A.M. Although I could still hear gunfire in the distance, the immediate area was very quiet. It was almost as if the war had moved away. I do not recall being hungry or even particularly thirsty, although as the day wore on I became very thirsty. I sat for about two hours until I finally saw someone, a lineman setting up telephone wire for battalion headquarters that were going to be set up in "my field." He was horrified when I told him how long I had been there and immediately went back to call for medical aid.

Two hours later, at about 10 A.M., the same lineman saw me still sitting in the field. With that, he returned to the rear and brought back the medics. They came in a jeep. They picked me up and placed me on my back on a stretcher, and placed the stretcher on one of the fenders and part of the hood of the jeep. Their moving me on to my back caused me the most pain that I had yet experienced since I was hit -- and more pain than I experienced until I had my bandages ripped from my hairy chest in the general hospital in England.

During the process of being moved away from the hedgerow I not only experienced excruciating pain, but I could also hear and feel air being drawn through the wound in my back. Whenever I was raised or raised myself away from the stretcher, I would re-experience the pain and the feeling of air being sucked through my back.

The medics also recovered another wounded man nearby. They placed his stretcher on the other fender. He had to lie face down because his buttocks were almost completely blown off by some shell explosion.

The bumpy ride over the rough farm roads was most uncomfortable. At one point, the jeep had to go through an opening in a hedgerow that was closed by a large wooden gate. The drivers feared that the Germans might have booby-trapped the gate, so they tied a long rope to it and attached the other end of the rope to the front bumper. The jeep then backed up and pulled open the gate which, fortunately, had not been booby-trapped. Had there been an explosion, I might have been wounded again, and perhaps killed.

In a short while the jeep arrived at a rear aid station. I was given 250 cc of plasma as a prevention against shock. Despite the extensiveness and nature of the wound, and the 28-hour period waiting to be picked up, I did not need any more plasma or blood at that time. I was also given a shot of morphine. I asked for water because I was so thirsty, but nearly choked on it. Several minutes later, I was turned over on my stomach so that my wound could be examined and dressed. Without the pressure against the back, I had considerable difficulty breathing.

Through all of this I was not especially uncomfortable or disturbed. However, when I looked at the persons who were looking at my wound, I guessed from the "Oh, my God!" expressions on their faces that I must have been seriously wounded. The wound was bandaged quickly, and I was taken back a little further to the rear to a field hospital.

The field hospital was a group of rather large tents. I was brought into one about the size of a circus side-show tent. I was met by a man who introduced himself as Major Alfred Hurwitz. He began questioning me, and the nature of his questions, and his calm and confident manner made me feel at ease. After the questioning, I was asked to sit up over the edge of the cot so that I could be X-rayed. As I recall, I did this mostly under my own power.

I felt that I had to urinate, so I was given an empty food can for that purpose. Somehow, I couldn’t urinate. Suspecting that I might be inhibited, Major Hurwitz left me alone in the tent. Still no luck. Finally, he asked me if I ever had a venereal disease which affected my urinary tract. I told him emphatically, no. They had to catheterize me. In retrospect, I know that my difficulty was due primarily to the effects of morphine.

I was taken into another tent, seemingly somewhat smaller, which was the operating room. The floor was the ground, and I am certain that some unsanitary animals had roamed over that ground not many days earlier. A rubber band was tied around my upper arm, a needle was inserted into my vein, some Sodium Pentothal was injected, and I was told to count to 100. I remember saying "3", and then fading pleasantly away. I believe that I was out for about 12 hours.

17 July 1944

I don’t know what time it was that I awoke from the operation. It must have been early morning--it was just beginning to get light. My head was clear but I was sleepy. I think I must have dozed off again for a while because when I awoke the few lights were out and it was quite bright.

Before I tell you anything else I’d like to describe the ward. It was a large tent--really two tents combined. There were about 45 or 50 patients in the ward, lined along the two long sides and through the middle. The flaps (sides) of the tent were rolled up and a large ceiling flap was open but still the place was fairly warm. Cots were our beds but I was still on the stretcher which was set on top of the cot. The cots were set on the ground--the only floor.

The door to my left was the entrance or exit to the outside--the door (just openings both of them) to my right led into the operating tent. Near the outside door was set the makeshift kitchen, with trays, cups, etc. The cooking however was done in a separate tent.

A crude table held the medical supplies and dressings. There was hardly room enough for a larger table and they hadn’t been in this place long enough to get well organized. They never stayed in one place long. There were three units to the hospital (this was no. 1). As one would empty, it would fold up and move to the front. The rear unit each time would do the same. The hospital landed D+2, some of the doctors D+1 and a few of the men on D-Day. Getting rid of all its patients never insured a unit of rest. It only meant moving again.

The first person I saw when I awoke was a nurse standing over me at the head of my bed. That was Sue. What her last name is I’ll never know. Everyone called her Sue (all nurses are at least 2nd Lt.). The doctors, the ward boys, and the patients all called her Sue and that was the name most frequently heard. She was on day duty while I was in the ward and she worked every minute of her twelve hour shift and often stayed four hours or longer to help on the night shift. Whenever the ward boys couldn’t handle something they’d call for Sue. The surgeons on their rounds wanted Sue to accompany them. She was the first person the patients would call for if they needed anything. And she was always there, very skillful and unbelievably patient. It must have been extremely trying for her. It was so hot and dry that everyone cried for water but very few were allowed to drink any because of the tubes and liquid in their stomachs. Men with punctured lungs were crying for cigarettes. And how she would argue with them for their own good. I never saw her lose her patience although the same procedure continued unabated all the time I was there.

Sue was blond haired--almost going on red hair, round pretty face, tall and pleasantly built. There was another nurse with her on the same shift who was surprisingly like Sue in appearance. The difference lay in a slight degree of attractiveness and height. Their hair was identical.

I didn’t care too much for the night nurses although they worked just as hard. Somehow, even though they were older, they lacked the tactfulness of the other two. The day before I left the hospital several apprentice nurses (fully registered and commissioned but not very experienced) came for practice.

There were ward boys whose equal I did not see in any of the rear echelon hospitals. During the day there were older boys. I don’t quite remember their names correctly -- one I don’t recall at all but of the other two--one was called Johnny and the other (a Mexican fellow) called (a guess at the spelling) Quere. There was also another fellow who seemed to be the chief non-com of the ward although he wasn’t around half of the time. The reason he wasn’t around, I believe, was because he was drunk most of the time. He was a stocky good-natured Irishman (I believe the name was O’Toole). He used to go around from bed to bed in his slightly inebriated condition trying to cheer the fellows.

The three main ward boys were called upon to do all sorts of things from shaving men to doing difficult colostomy dressings. The ward boys at night were of no lesser quality although they were much younger--the three of them were 19 years old, two of them a few months younger than I.

One of these boys was also called Johnny. He was short, stocky and fuzzy haired and he used to call me fuzzy. They all did. I don’t blame them either. I had more hair on my unshaven face than I did on my nearly shaven head. The other two fellows were tall---one called Silvers--the other Ort. They all worked hard.

There were four majors around the hospital--three in charge of surgical teams and one in charge of the whole unit. Major Hurwitz had done my surgery and naturally I got to know him a little. He was especially interested in my case because he had done some necessary experimental work on me. However, the first thing he asked me was if I had been able to urinate. The morphine had worn off and I was able to relieve myself. Major Hurwitz was from Boston but that’s all I know of his civilian life. He must have established a good reputation with the hospital because everyone spoke well of his work. He did mostly chest cases. The unit did only chest and abdominal surgery.

Three days after the operation, Major Hurwitz had to leave for another unit and I was left in care of Major Ben Reiter (or Ryder) who handled mostly abdominal cases. He and his assistant Captain Smith used to check me every day.

From what I saw, Maj. Reiter was very capable. On either side of me were two fellows (an enlisted man on my left, a captain on my right) who had almost identical wounds. Rifle or machine gun fire had punctured part of the small intestines of both. Maj. Reiter each day would drain the wastes from that puncture and at the same time treat it so that it would heal. Within seven days both men were sent to the operating room to be sewed up. It was no longer necessary to have the intestines protruding.

That captain was one of the most patient men I have ever seen. He lay in the same position (on his back) for seven days without being turned to either side. He was fed through his veins and rarely got more than a sip of water to drink. It wasn’t until the fifth day that he was allowed to have any fruit juice. I never heard him complain.

Many men (in fact most of the patients) were fed through their veins. Some got whole blood, plasma, saline solutions or sugar solutions. Very often it was difficult to find the veins and painful probing had to take place. I was very fortunate. I had to have no intravenal feeding and the tube in my throat and stomach was removed the second day. By the fourth day they put a full meal in front of me.

July 15, 1944 (evening)

Combat History of Word War II

, Chapter IV Normandy, By Major General Butler B. Miltonberger, Former Commanding Officer, 134th Infantry Regiment and Major James A. Huston, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University Transcribed by Roberta V. Russo, Palatine, Illinois:

For the 1st Battalion it was Companies A and B in that twilight assault against the final defenses of Hill 122. Captain McCown of Nebraska seemed to be everywhere, urging his platoon on, co-ordinating the welcome support of Sherman tanks, personally directing artillery fire against key enemy positions. His example extended to others and carried the company with it. Such an example was that of 2nd Lt. Constant J. Kjms of New York, a rifle platoon leader, a junior officer whose stature grew to command the respect of his whole company and the admiration of all who learned of his actions. Shell fragments had torn into his arms and face, but it would take more than that to put him out of action. He continued at the head of his platoon throughout the day’s fighting.

Captain Lorin McCown "Larrupin Lou" as all-state tackle on Beatrice (Nebr.) high school football teams back in 1929 –– 1931 –– was carrying his A Company right with him in his drive to reach the objective. Repeatedly he would leap onto a tank, and shout words on encouragement to his men as they drove unwilling bodies forward. He led the final phase of the attack from the open turret of a tank. Defiant of direct artillery fire, mortars, machine guns, he breathed a determination which seemed to spread to all those who could hear or see him. As they were driving the task to completion, however, a burst of machine gun fire caught him in the abdomen. It was a severe wound, but the captain insisted on staying up with the fighting until Colonel Boatsman ordered his evacuation. Lieutenant Kjems was carrying on with an aggressiveness which had become habitual.

Among the patients in the ward was my company commander suffering, I thought, from shock and a fairly serious intestinal wound. . . . During the first day of fighting the company commander, (Note this is Capt. McCo wn) executive officer and platoon leader . (Note this is Lt. Kjems ) were wounded)

The battalion Protestant chaplain whom I knew quite well visited the floor several times, usually looking as if he had spent a rough time in a foxhole. He told me about other fellows in the outfit.

The conditions of the patients in the ward varied, all were seriously injured. But only one died and he passed away so quietly that no one realized it for several hours.

Of all the patients in the ward, I was one of the two who after a few days was able to move himself a little under his own power. After three days and with some difficulty I was able to turn on my right side. The other man was able to turn both ways and raise himself quite a bit. That’s right, I was able to raise myself a little on my right arm.

But that first day, I still had the tube in my stomach but I wasn’t too uncomfortable. I had a drink or two three times during the day. They had to give me water to take sulfadiazine tablets which were given to me four every four hours along with a shot of penicillin.

During the day they lifted me from the stretcher, removed it, and set me directly on the cot.

Except for the bustle of everyone working, there was general calm toward evening. As it grew dark lights went on (two crude lights on each side of the tent) and stayed on all night. Our sleep was disturbed that night when some heavy piece of artillery fired. We must have been directly in line with it and very close in front of it. The blast really shook us.

18 July 1944

Today’s installment will be the last because the news from this date until July 23 when I landed in the 52nd Gen. Hospital in England is not enough to write day by day.

One of the first things done a year ago today was the removal of the tube in my stomach. That was a relief because I was allowed to drink a little more water. I was even given a little fruit juices which were especially relieving to my mouth. My teeth weren’t brushed all the time I was there. By 20th of July, I was allowed to eat a full meal. After not having eaten for four days, I had a little difficulty trying to eat so much. Sulfa drugs were stopped on the 20th but I still got penicillin until I left.

Excepting for the cooling effect of an occasional rain, we were generally too hot for comfort. It was a job even keeping a white sheet over my naked body.

I was anxious to leave the hospital. Nothing was being done for me--nothing could be done--except for the giving of shots and sulfa. That could have been done elsewhere and I could have been out of their way. I asked when I was going to leave. To my disappointment, they said not right away. They said that chest cases had to be kept at least a week before evacuation. Yet, on the third day, both Maj. Hurwitz and Maj, Reiter sounded my chest and pronounced it clear.

I was also curious to know where I was going. They told me that I was going to return to the United Kingdom and then most likely go by plane to the U.S. I liked that. Major Hurwitz said that I might have been shipped earlier but he had removed my spleen and that it was necessary to rest a long time after that.

Up until this time I had no idea what damage the mortar had done to me nor what had been done to me in the operation. By chance I got hold of my chart which one is not supposed to see but which I read so many times that I practically memorized it.

Here’s the damage done by the mortar:

1. Tore my diaphragm about 4 ? inches--luckily along the line of muscles and not severing them.

2. Lacerated my spleen to the extent that it had to be removed.

3. Punctured the lower left lobe of my lung.

4. Threw in small bits of shrapnel. (Despite the fact that the shell hit about a foot away from my back, most of it was blown away and not into me. The blast tore my skin open.)

Here is the treatment done in one operation.

1. Removal of 4 inches of rib so that he could get inside of me.

2. Sewed my diaphragm.

3. Expanded (rather than collapsed) the lung so that it would heal by itself.

4. Removed the spleen (a major operation in itself).

5. Removed shrapnel (except for two tiny pieces too close to my lung to chance removal).

6. Cleansed the wound.

7. Made a primary closure of the wound.

8. Dressed the wound.

Later in England the bandage was removed every other day and the wound was cleansed. When it began to heal from the inside, they sent me to the operating room to have it sewed. I probably experienced more pain after being sewed because then the flesh began to grow together quickly and at each time I turned too hard I would pull painfully at the freshly grown flesh. Yet within twelve days the stitches were removed and that is nothing short of amazing, especially since it held together after the stitches were removed. The wound originally was about as long as this paper, about half as wide and about as deep as it was wide. The healing was nearly miraculous.

To give some idea as to the effectiveness of the operation:

1. The diaphragm never stopped functioning.

2. The lung held ether three weeks later when they sewed me up.

3. My splenectomy never bothered me. Other similar cases were immobile for over two weeks developing ulcers and lung trouble.

4. The wound was so well drained that despite the slightly cloudy X-Ray no liquid was found in me when they tried to aspirate me in England (sticking a blunt needle into the chest to draw out liquid ?hemothorax? formed during a severe injury. Very painful.) I’ve seen them draw as much as 1500 c.c. out of others at one time.

5. Final proof of its effectiveness is my own present strength, superior lung capacity than before I was wounded, my heart is in excellent condition.

Back in the field hospital, my bandage was itching terribly. The doctors knew it but were afraid to change it. The operating room was the only sterile room and they couldn’t take me back there to re-dress the wound.

Finally on July 22 the order for my evacuation was O.K.’d. Maj, Reiter signed the paper. It came rather unexpectedly and they didn’t have time to shave or wash me and I was filthy. Before putting me on the ambulance they gave me two more shots of morphine--and I knew what to expect.

The ambulance took several of us to an airstrip. After about an hour I was loaded on a C-47, transport plane, near the tail and at the top of the plane. The ride lasting about an hour was very smooth despite poor weather. There were litter-bearers waiting at the hospital airstrips and they took us immediately into our ward--a tent. The hospital unit presently occupying the hospital was to move out the next day. There was confusion in that place that night.

The next morning we were loaded on a hospital train.

When they brought me in Ward 27 of the General Hospital (52nd) it was like coming into a different world. Nice white hospital beds, bright waxed floors, quiet peaceful atmosphere, a radio softly playing. . .

This is the end of Bob Goldstein’s journal about being in France with the 134th Infantry. After recovery at the 52nd General Hospital in England, Bob received a promotion and was transferred to a different "outfit." With his new unit he participated in the Ardennes campaign (Battle of the Bulge) and the Rhineland campaign.

After the war Bob Goldstein received his B.S. degree from Pennsylvania State University in 1948. He married Gay Swartz in 1948.

Bob Goldstein, became a pioneer in the field of Audiology and Acoustics and was the first person granted a Ph.D. in Audiology from Washington University in St. Louis in 1952.

During his prolific career, under the name of "Dr. Robert Goldstein" he published over 120 papers, 35 abstracts, and participated in lectures, conferences and workshops. In 1999, he published a textbook entitled Evoked Potential Audiometry: Fundamentals and Applications.

He was president of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association from 1971 to 1972, and received many awards including: Recipient of Research Career Development Award, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness; Honors of the Missouri, Wisconsin, and Nevada Associations of Speech-Language-Hearing; and Fellow and Honors of American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

He also was a member of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Fellow in the American Graham Bell Association of the Deaf, American Clinical Neurophysiology Society, and the International Evoked Response Audiometry Study Group.

In 1999 he developed complications from the wound he received with the 134th Infantry. Bob Goldstein died of those complications in December 2000.

I thank Roberta Russo for posting Bob Goldstein’s journal on her web site. If anyone remembers him, I would be like to hear from you. You can contact me at my home in Las Vegas, Nevada or at Miradad3124@aol.com.

Mark H. Goldstein (son of Pvt. Robert ("Bob") Goldstein, 1st Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 134th Regiment).

| View My Guestbook |